Why Do Leaves Change Color?

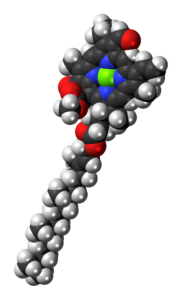

Throughout spring and summer, chlorophyll (the molecule seen above which allows trees to absorb sunlight and produce nutrients) is made and replaced constantly.

However, as days grow shorter, “cells near the juncture of the leaf and stem divide rapidly but do not expand,” reports Accuweather.com. “This action of the cells form a layer called the abscission layer.

“The abscission layer blocks the transportation of materials from the leaf to the branch and from the roots to the leaves. As green Chlorophyll is blocked from the leaves, it disappears completely from them.”

That’s when vivid yellow xanthophylls, orange carotenoids and, due to a different process, red and purple anthocyanins emerge.

Yellow comes from Xanthophylls (compounds) and Flavonols (proteins) that reflect yellow light. Flavonols are what give egg yolks their vivid color.

Orange is found in leaves with lots of beta-carotene, a compound that absorbs blue and green light and reflects yellow and red light, giving the leaves their orange color. Though always present in the leaves, Carotenoids and Xanthophylls are not visible until Chlorophyll production slows.

Red comes from the Anthocyanin compound. It protects the leaf in autumn, prolonging its life. Anthocyanins are pigments manufactured from the sugars trapped in the leaf, giving term to the vernacular expression, “the leaves are sugaring up.”

The best fall color occurs when days are warm and nights are clear and cold. California’s cloudless skies and extreme range of elevations (sea level to 14,000′) provide ideal conditions for the development of consistently vivid fall color, as seen in these reports.

Peak fall color will begin appearing in the Eastern Sierra above 9,000 feet (you can drive right to it) during the last two weeks of September.

Predictions

About this time, each summer, Google Alerts sends links to articles containing “Fall Color.”

It’s fascinating to read these Google Alerts and learn whether fall color is being predicted to be early, late or about normal, and why prognosticators think so.

Most fall color forecasters are meteorologists who base their predictions on measured precipitation and temperatures. So far so good, but then they get out of their lane and guess what effect too little or too much rain, too warm or too cold autumn days might have on forthcoming foliage.

From years of observation, I’ve found that more or less precipitation tends to lengthen or shorten the display of fall color. It does not make it appear earlier or later. With more water, deciduous leaves last longer on branches. With less water, they dry up and fall off sooner.

It’s not water or lack of it that causes color change, it’s the seasonal change in temperature and light. As days shorten due to the Earth’s rotation, leaves get less light and nights become colder.

At first, the change is imperceptible, but then, gradually, the production of green chlorophyll slows and underlying yellows, oranges and reds emerge. Temperature intensifies or dulls fall color, but it does not make it appear earlier or later. Warm days and cold nights stimulate the most vibrant displays.

So, when is fall color predicted to appear?

- Connecticut – one source says early, another says late, both agree that drought is the cause

- Massachusetts – late

- New England – Yankee magazine estimates it will peak in any time from Oct. 5 – 22 or Oct. 12 – 28 or even as late as early November.

- Wyoming – normal (early to mid Sept., continuing to mid Oct.)

- Ohio – late

- Minnesota – early

As for California? It’s too early to say.

Irvine Regional Park

On a recent visit to Orange County, Michelle and Ron Pontoni visited Irvine Regional Park to find autumn still happening in January.

Western sycamore (Plantanus racemosa), red willow (Salix laevigata) and Toyon or California holly (Hereromeles abutifolia (Lindl.) were all at peak along dry Santiago Creek.

They were there to visit the Orange County Zoo which rescues injured, orphaned, confiscated and other native animals no longer releasable into the wild. They include American black bear, mountain lion, bald eagle, kit fox ocelot, beaver, great horned owl, porcupine, coyote, and turkey vulture among their decidedly native selection.

While observing a trio of goats, the Pontonis realized the goats were waiting for lunch. The South Coast breeze would rise and blow delicious sycamore leaves to them from branches, reminding Michelle of wedding guests vying to catch a bridal bouquet, all huddled together and keeping their eyes on the prize of a fluttering leaf. She said, “the only hope for the smaller goats was if several leaves fell at once.

“On that breezy day, piles of sycamore leaves lined every pathway and pen, except theirs. They are good housekeepers,” she wrote.

Western sycamore are a gorgeous fall color tree for Southern California, but grow throughout California up to 4,000′ in elevation. They flourish near wet ground (stream and meadow edges) in valleys, foothills and mountains. Their ball-shaped fruit attract birds, including the Santa Monica Mountains’ population of naturalized Nanday conures (parrots).

Native people used the sycamore for many purposes, including their houses, utensils, to eat and to wrap bread for baking.

Michelle recommends the two-mile hike along the Chute Trail to Barham Ridge Trail lookout for a broad view of Santiago Creek and its golden grove of red willows, though be watchful for mountain bikers who pedal up the Chute Trail for an exhilarating ride down the steeper Ridge Chute Trail. Though they were courteous to the hikers, Michelle and Ron couldn’t help feeling like they were an unexpected concern to the riders.

Parking at the regional park is plentiful and cheap. $3 on weekdays, $5 on weekends. Add $2 for zoo admission.

- Irvine Regional Park (587′) – Peak (75 – 100%), GO NOW!

Holiday Ornaments

Numerous ornaments decorate trees in late autumn.

There are, of course, the manmade type that are hung on Christmas trees, but also many types of colorful berries grow in the wild and in our gardens … crimson toyon, vermilion pyracantha, purple beautyberries and the yellow, orange and red fruit of the Madrone, Arbutus menziesii (Strawberry Tree).

Today, Phil Reedy and I had the same idea. Instead of traveling afar to find fall color, just go outside and discover it in our yards. In addition to arbutus berries and blossoms, Phil noticed that all the sycamore in Davis had lost their leaves with just a lone flowering pear leaf nestled among their tan remains. It’s now past peak there and peak has dropped to sea level.

Eastern vs. Pacific

When it comes to dogwood (Cornus), all the native trees in California have white bracts (flowers) while those in the east are pink. So, if you see a pink dogwood anywhere in California, it is a transplant from the eastern U.S.

In Yosemite Valley, a few pink-flowering dogwood (cornus florida) were planted by residents and have been allowed to remain growing in the park. One at The Ahwahnee is often confusing to park visitors because of the pink color tinting its stems and showy red fruit.

In springtime, eastern dogwood have profuse displays of pink bracts. They look like flowers, but they’re not. Bracts are leaves which have evolved to appear to be flower petals. They help in attracting pollinators. The dogwood’s actual flowers reside at the center of the bracts and have their own modest petals.

Pacific dogwood (cornus nuttallii) are beautiful in their own right and the banks of the Merced River are lined with these flowering white trees in May.

So, if you happen to see a pink dogwood in Yosemite National Park, it doesn’t belong there. And, if you think otherwise, then you’re just barking up the wrong tree.

Why Don’t Evergreens Lose Their Leaves?

Actually, they do. It just doesn’t happen all at once, with few exceptions.

Evergreen trees have both broad leafs and needles. Madrone, magnolia and photinia are examples of broadleaved evergreens, while pine, fir, cedar, spruce, and redwood have needled leaves.

Evergreen needles can last anywhere from a year to 20 years, but eventually they are replaced by new leaves. When that happens, the old needles turn color and drop, but not all together and not as dramatically as deciduous trees (e.g., maple, oak, dogwood, alder, birch).

The reason needles are green is that they are full of chlorophyll which photosynthesizes sunlight into food for the tree. It also reflects green light waves, making the needles look green.

Needles, just like deciduous leaves, contain carotenoid and anthocyanin pigments. You just don’t see them until the green chlorophyll stops being produced. Once that happens, hidden carotenoids (yellow, orange and brown) emerge, as is seen in the above photograph.

Additionally, red, blue and purple Anthocyanins – produced in autumn from the combination of bright light and and excess sugars in the leaf cells – also emerge once the chlorophyll subsides.

Yes, even evergreen leaves change color… eventually.

Evergreens that drop leaves at one time include the: Conifers Larch, Bald Cyprus and Dawn Redwood.

In snowy regions, evergreen trees are able to carry snow because the waxy coating on needles, along with their narrow shape, allows them to retain water better by keeping it from freezing inside (which would otherwise destroy the leaf).

Needles also prevent snow from weighing down and breaking branches. Finally, needles allow an evergreen tree to sustain the production (though slowed) of chlorophyll through winter. Whereas, broadleaved deciduous trees would be damaged if they kept producing chlorophyll and didn’t drop their leaves.

Evergreen trees do lose their leaves and the leaves do change color. It just isn’t as spectacular.

Why do Deciduous Trees Lose Their Leaves?

It’s survival not just of the fittest, but of the wisest.

Deciduous trees drop their leaves in order to survive. As days grow shorter and colder, deciduous trees shut down veins and capillaries (that carry water and nutrients) with a barrier of cells that form at the leaf’s stem.

Called “abscission” cells, the barrier prevents the leaf from being nourished. Eventually, like scissors, the abscission cells close the connection between leaf and branch and the leaf falls.

Had the leaves remained on branches, the leaves would have continued to drink and, once temperatures drop to freezing, the water in the tree’s veins would freeze, killing the tree.

Further, with leaves fallen, bare branches are able to carry what little snow collects on them, protecting them from being broken under the weight of the snow. So, by cutting off their food supply (leaves), deciduous trees survive winter.

The fallen leaves continue to benefit the tree through winter, spring and summer by creating a humus on the forest floor that insulates roots from winter cold and summer heat, collect dew and rainfall, and decompose to enrich the soil and nurture life.

It’s a cycle of survival, planned wisely.

The Science of Changing Leaves

A couple of years ago, Smithsonian.com posted a time-lapse video of leaves transforming from chlorophyll-filled green to tones of yellow, red and brown. The video was accompanied by an article explaining how leaves change color and some misconceptions about the process.

The video was created by Owen Reiser, a mathematics and biology student at Southern Illinois University Edwardsville. Reiser, Smithsonian.com reports, took 6,000 photos of leaves to weave the video together.

Leaves that change due to the loss of chlorophyl as a result of shorter days and fewer nutrients tend to turn orange or yellow. Though David Lee, Professor Emeritus of biological sciences at Florida International University and author of Nature’s Palette, The Science of Plant Color, says that many yellow and orange leaves do not change the same way as red leaves.

Lee states in a Smithsonian.com article that the breakdown of chlorophyll in leaves does reveal yellow and orange (carotenoids) hidden beneath, but that red (anthocyanin) pigments are produced within the leaves as they die.

There are two thoughts as to why this happens. One is that the red color is a defensive measure to make the plants appear unhealthy as the leaf dies, protecting the tree from plant-eating bugs and animals which are conditioned not to eat red foliage.

The other thought is that red is a form of photo protection. Horticulturist Bill Hoch, Smithsonian.com reports, believes red’s wavelength helps shield the leaf by absorbing excess light allowing the plant to more efficiently remove nitrogen from the proteins that are breaking down and send that nutrient back to tree limbs and roots, saving as much of it as possible before winter.

Whatever the cause, the result is spectacular and less than a month away from being seen in California.

Why do Leaves Change Color?

Leaves on deciduous trees change color in autumn from green to various hues of lime, yellow, gold, orange, red and brown because of a combination of shorter days and colder temperatures.

Throughout spring and summer, green chlorophyll (which allows trees to absorb sunlight and produce nutrients) is made and replaced constantly.

However, as days grow shorter, “cells near the juncture of the leaf and stem divide rapidly but do not expand,” reports Accuweather.com. “This action of the cells form a layer called the abscission layer.

“The abscission layer blocks the transportation of materials from the leaf to the branch and from the roots to the leaves. As Chlorophyll is blocked from the leaves, it disappears completely from them.”

That’s when vivid yellow xanthophylls, orange carotenoids and, due to a different process, red and purple anthocyanins emerge.

Orange is found in leaves with lots of beta-carotene, a compound that absorbs blue and green light and reflects yellow and red light, giving the leaves their orange color.

Yellow comes from Xanthophylls and Flavonols that reflect yellow light. Xanthophylls are compounds and Flavonols are proteins. They’re what give egg yolks their color.

Though always present in the leaves, Carotenoids and Xanthophylls are not visible until Chlorophyll production slows.

Red comes from the Anthocyanin compound. It protects the leaf in autumn, prolonging its life. Anthocyanins are pigments manufactured from the sugars trapped in the leaf, giving term to the vernacular expression, “the leaves are sugaring up.”

The best fall color occurs when days are warm and nights are clear and cold. California’s cloudless skies and extreme range of elevations (sea level to 14,000′) provide ideal conditions for the development of consistently vivid fall color, as seen in these reports.

Peak fall color will begin appearing in the Eastern Sierra above 9,000 feet (you can drive right to it) some time during the last two weeks of September.